A story about America

A hymn of praise for the United States of America. But also a warning, a farewell and the end of my newsletter from Washington D.C.

Dear readers,

After a longer break, it’s time for the finale: this is the last newsletter from Washington D.C. My time here is coming to an end and my Master’s degree at Georgetown University is complete. I am moving to Europe, where exciting developments are taking place that I want to help shape.

Thank you for the past months and for reading and sharing my publication. Thank you for the comments and feedback, and I want you to know that it has been a pleasure to write and report for you from Washington D.C. every week.

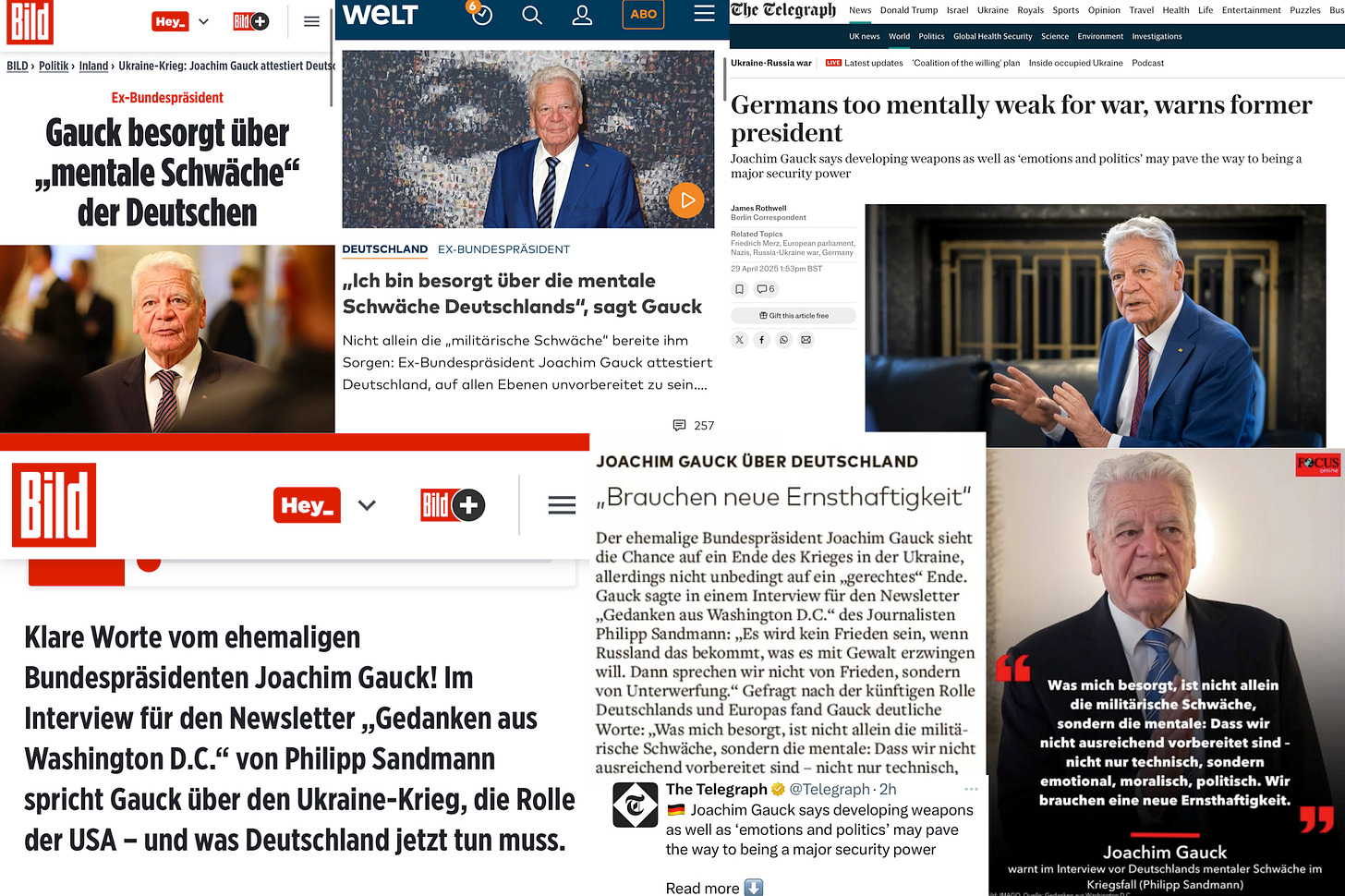

I launched Thoughts from Washington D.C. before the U.S. election in November 2024, and since then over 500 people have subscribed to my newsletter. At the end of April, an interview with former German President Joachim Gauck generated a great deal of discussion, not only in Germany but also in international media. I would never have thought that my newsletter would be quoted in a printed newspaper.

This shows that starting something new is worthwhile. I have the greatest respect for the many freelance journalists who are on the lookout for good stories every day. Even if my path may not lead me back to journalism, I will always remain loyal to this profession.

And, there will be a new newsletter. From Germany. More on that soon. I would be delighted if you remain loyal to me as readers. Of course, you will also have the opportunity to unsubscribe. An important information for my paying subscribers: your payments will be paused for the next few weeks (I’m taking a little break).

But now, my last article from Washington D.C.

It is about a country with that famous idea of social advancement. But it is also about a country that no longer exists in this form. Maybe, the idea of America will remain. However, future generations, the talented and amazing people I was able to meet during my studies, will have to breathe new life into it. And perhaps something of the basic idea of America will remain: that the U.S. is a country of immigrants and a country of (unlimited) opportunities.

America is simply great!

The first time I traveled to the U.S., I was 14 years old. As I approached New York by plane, I saw the sea of lights and the avenues and streets organized in a drawing board pattern.

I was trembling. I was excited. Arriving. In America.

I was picked up at John F. Kennedy Airport (JFK) by a good friend of my grandmother. Uschi. Uschi was born in the east of Germany. She met an American. They got married. Uschi moved to the U.S. Today she speaks German like an American and English like a German.

Uschi and Jack live in Princeton. Back then it was February. Superbowl final time. They made chili for dinner. Their car was a Ford Crown Victoria. It smelled of vanilla. The car was as big as a ship. The engine hummed quietly but powerfully.

We entered the house via the garage. Garages in the U.S. are often a room that would pass for a guest room in Germany. Garages are organized and clean, sometimes even carpeted. Inside, I found a large refrigerator and neatly organized cans of Coca-Cola. I was thrilled. I was in America.

My second visit to the U.S. was also magical. It was July 2007, I was 17 years old and was able to visit Washington D.C. and New York for two weeks as part of a “global young leaders program”. It was one of the most exciting political times ever.

At that time, almost nobody in Germany had heard of Barack Obama.

In the U.S., however, they had. Even though not many people thought he would become president, it was somehow clear that the country wanted a big change after the Bush years. Just one year later, Obama would become the Democratic candidate for the presidential election. He went on to win the 2008 US election against John McCain. A historic moment.

The feeling from back then, that moment of arriving in America, has never gone away. Not even 20 years later.

It was an absolute luxury and a great privilege for me to be able to fly across the Atlantic as casually as if it were a train ride from Munich to Hamburg. A journey that used to take people weeks on a ship. A route that remains a dream for many people today.

I was able to travel to America many times in recent years. It was always something very special for me, every single time. After the long summer of 2024 in Germany, I thought to myself: I’m going home soon. To America.

You can describe the U.S. in many different ways and I wouldn’t dare to claim that I know this country with all its differences and nuances. But I have seen some parts of this country and one thing is the same in almost every state: the air conditioning. Or “A/C”.

Americans like it cold indoors.

The American air conditioner, it runs 24/7. No, it roars.

Just like the economy. It works day and night. Air conditioning in the U.S. is only really good when it’s cold outside, but even colder inside. It’s all rather strange for Europeans. Or as one would say these days: “The European mind cannot fathom...”

I never quite understood it either (and often almost froze to death), but I learned that the A/C is part of the country, just like Thanksgiving.

The United States - a fragile country?

However, the physical chill that one can live with has increasingly become a political and social chill in recent years. The comparison may seem overused, even pathetic, but it is true.

Over the past few weeks, I have been working intensively on the topic of social contracts as part of my studies. A social contract is different from a country’s constitution and cannot be found in any official document. Nevertheless, a social contract is the framework that holds a country together.

In the U.S., this contract is (was) the promise of social upward mobility.

The American Dream.

From rags to riches. It worked very well for many decades.

But a few years ago, something changed in the U.S. that is much bigger than Donald Trump. On the one hand, the social contract is in danger of breaking down because the above-mentioned promise no longer applies and social advancement is no longer possible for more and more Americans. On the other hand, the U.S. has become an increasingly “fragile” state.

So what does that mean?

When we talk about “fragile states”, we first think of countries such as Sudan, Syria or Afghanistan. And yes, these states are indeed among the most fragile in the world. Some can even be described as “failed states”, i.e. states that are no longer able to assume even a minimum of responsibility for the security of their citizens.

There are various designations and categories for countries that are classified as fragile. The World Bank, for example, has two:

Countries with a high degree of institutional and social fragility, determined using indicators that measure the quality of policies and institutions and the manifestations of fragility.

Countries affected by violent conflict, determined on the basis of a threshold value for the number of conflict-related fatalities in relation to the population.

While there is no war in Kosovo, for example, the country is nevertheless on the list of fragile states because the World Bank concludes that there is institutional and social fragility there.

In addition to the World Bank, there are also other organizations that deal with this topic. For example, the “Fund for Peace” publishes a “Fragile States Index” every year, in which almost all countries in the world are ranked according to their fragility. In 2024, Somalia was in first place (most fragile) and Norway in 179th place (least fragile).

But why write about these fragile states when the topic is the U.S.?

Because an interesting (and worrying) trend can be observed in the USA.

Eighteen years ago, in 2007 (shortly before the financial crisis), the U.S. was ranked 159th on the index and was surrounded by countries such as Italy and France. At that time, the U.S. was considered less fragile compared to Germany, which in turn was higher on the list (i.e. more fragile, in 153rd place).

In 2024, the U.S. was ranked 141st, a difference of exactly 18 spots. On average, the U.S. has therefore dropped one spot every year since 2007 and has moved towards increasing fragility. In 2024, Argentina, Chile and Qatar were considered less fragile than the United States of America.

Now, it must be said that such lists are not a particularly good indicator of the future. In other words, some countries (such as Ukraine) may not have been considered particularly fragile at a certain point in time, but then a war broke out that changed everything.

The situation was similar in Syria before the Arab Spring: The analyses before 2011 did not necessarily conclude that a civil war was imminent in Syria. Today, the country is destroyed and it will take many years before Syria is rebuilt and remains stable.

But let’s take a closer look at the U.S. and why fragility is increasing in the country.

An indication can be found in the Fragile States Index of 2023, which explains that the Cohesion Indicators in most democratic countries deteriorated sharply between 2007 and 2020.

Within this group of democratic nations, the U.S. has by far the worst values. The interesting thing is that the figures can only partly be attributed to political factors.

What actually makes the U.S. an increasingly fragile state: Mass shootings and rampages (e.g. in schools).

It says in the report:

Stresses remain extremely high by historical standards, and the United States is by far the most worsened within this group.

In 2022, amidst continued political polarization, gridlock, and brinksmanship, the United States had the highest number of mass shootings ever recorded in a single year, according to a Mother Jones investigation, at schools, workplaces, places of workshop, and neighborhoods.26 This creates vulnerability to a potential shock.

Because even if a country is not fragile, if cohesion has worsened steadily over a decade, then when a shock such as a global pandemic eventually does hit, that country may not have the social capital necessary to mobilize the collective response to manage the crisis and prevent it from cascading across the social, economic, political, and security indicators.

Basically, the U.S. is losing stability, because the state is unable to prevent mass shootings. The state is not able to fulfill its most fundamental task: The protection of its own citizens.

The future

Let me be clear: I am not leaving the U.S. with bad blood.

Quite the opposite.

I have gotten to know a country that is facing its biggest changes since the end of the Second World War. But after a few months of Trump, it is also clear that the U.S. President won’t be able to deliver on many of the things he has promised. The plan to end Russia’s war against Ukraine in one day has not only failed miserably, but Trump has allowed himself to be downright outplayed by Russian President Putin. Quite a bad start in terms of foreign policy.

In addition, Trump’s arrogant disregard for the constitution and his disregard for laws and norms will cause enormous damage to his country.

But of course, Trump also has approaches that make sense.

If you look at his trade and economic policy, it becomes clear that Trump has understood that Americans are simply consuming too much. In simple terms, excessive consumption creates a massive trade deficit, because many of the (cheap) products have to be imported (from China).

Trump recently said in an interview that a child in the U.S. does not need 30 dolls to play with, but that two would be enough. He could never have said something like that during the election campaign. In the future, however, the real issue in America will be to reduce debt (public and private). That is a major task.

My final prediction: Americans will increasingly (have to) ask themselves who they’re actually working for, what they are fighting for and what is important to them.

In America, you earn more money on average than in Germany. That is true. However, there is no social safety net. What I mean by that is: if a monthly salary is lost or someone is ill for longer than a week, then the state doesn’t step in. In other words, the social contract in the U.S. does not include a welfare state.

That means that if the promise of social mobility no longer applies and the welfare state never existed, then what exactly does that mean for the identity of the U.S.? What role can and should the state play in the future? What do people expect from those who wield power?

The Liberal International Order, which the U.S. played a key role in shaping after the end of the Second World War, is facing monumental change and possibly even its end. We should all have an interest in the U.S. doing well in the future. What the U.S. has done for us in Europe after the horrors of war has helped to shape our future.

Perhaps it is now time for us to do something for the U.S. too. In any case, it was a dream come true for me to be able to live in this great country.

Goodbye, USA.

Philipp Sandmann

What a bittersweet read but beautifully articulated!